By Jackie Hajdenberg

(JTA) — Emily Talento grew up with Jewish friends and relatives on Long Island, attending Passover seders, bar and bat mitzvahs and Sha

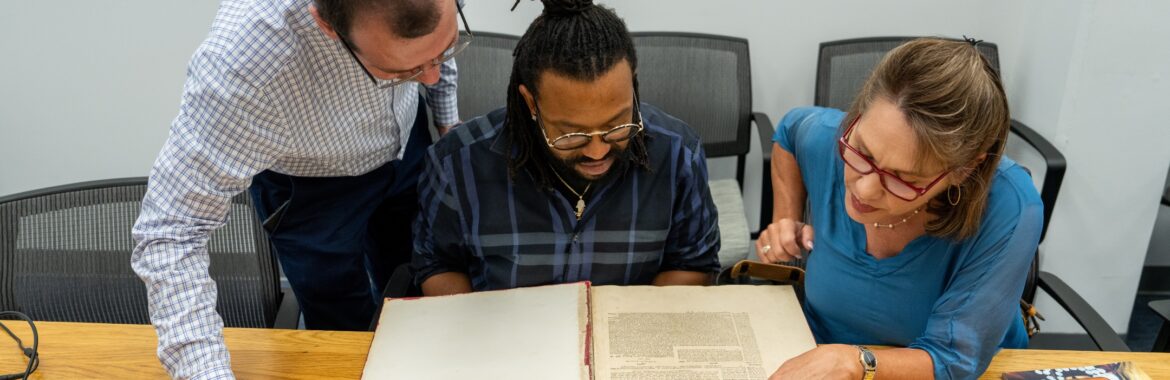

Christian students enrolled in the master’s program for Jewish studies at Yeshiva University read a piece of text from the book of Shemot, or Exodus, while on a tour of the campus guided by Jewish educators. (Courtesy Yeshiva University)

bbat dinners. When she arrived at Cedarville University, a private Baptist university in Ohio, she found herself explaining Jewish traditions to her many classmates who had never met a Jew before.

Now, Talento is continuing her Bible studies at a religious university. But it’s safe to say that she won’t encounter the same lack of knowledge about Jews this time. That’s because she’s one of eight Christian students embarking on a course of study at Yeshiva University that’s designed just for them.

In the two-year Hebraic Studies Program for Christian Students at the Modern Orthodox flagship, Talento and her cohort will take courses on Jewish history, biblical Hebrew, post-biblical literature and more.

“I’m excited that everything is coming from the Jewish perspective,” Talento said.

The new program is a joint initiative of Y.U. and the Philos Project, an organization that says it “seeks to promote positive Christian engagement in the Near East.” Philos is a partner of Passages — a Birthright-style program that brings young Christians on group tours of Israel — and it also organizes Christians to demonstrate against antisemitism.

The launch of the Christian students’ program is a sign of a growing bond between Orthodox Jews and religious Christians, who have increasingly found common cause on everything from conservative domestic politics to support for Israel. It is also an experiment in whether a school founded more than a century ago to accommodate the observances and sensibilities of Orthodox students in a majority-Christian country can now create an intentional space for Christians to study Judaism as well.

“Within the broader Protestant world, but particularly evangelicals, there’s been, I’d say in the last 50 years, just a really intense interest in the Jewish context of the New Testament, in particular Second Temple Judaism,” said Daniel Hummel, a historian of American religion and the author of “Covenant Brothers: Evangelicals, Jews, and U.S.-Israeli Relations.” (Philos, while founded by an evangelical Christian, identifies itself as ecumenical.)

That interest, Hummel said, has required encounters with Jews. “That’s sort of been the pattern,” he said. “You learn from Jews about their beliefs, and then you sort of take that thinking back to the New Testament texts, which then reshape how you read those texts.”

The program is part of an existing master’s degree program at Y.U.’s Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies. Y.U.’s undergraduate programs are separated by gender, are explicitly geared toward Orthodox Jews and combine traditional Jewish text study with a secular college education. But the university’s graduate programs, including Revel, are open to non-Jews, and Revel describes itself as a “genuinely non-denominational school.”

This year’s “pilot class” of eight Christian graduate students, who come from a mix of evangelical, Pentecostal and Baptist backgrounds, began with Hebrew Bible courses this summer. The students hail from California, Texas, Nebraska, Virginia and Mozambique. Five students are studying remotely, and three plan to be on campus in New York beginning in the fall semester.

“Our real goal is for the Christian students to gain a deeper understanding of the Jewish roots of Christianity,” said Jonathan Dauber, Revel’s director of external programming and Y.U.’s head of the Philos partnership. “It’s also a program that’s meant to foster dialogue and understanding between Jews and Christians because the Jewish students and Christian students are together.”

What sets the new program apart from the rest of the Jewish studies school is that it is a “curated pathway” for Christian students, Dauber said — though aside from the biblical Hebrew classes, the students will take the majority of their courses with other Revel students. Y.U. also hopes to create space outside of the formal classroom where students can interact, such as on a museum visit or via other cultural activities.

Some Christian groups and individuals have appropriated various Jewish rituals for Christian purposes, hosting “Christian seders,” blowing a shofar, or ram’s horn, at prayer or marketing Christian takes on the mezuzah. Those practices have also sparked backlash from both Jewish and Christian clergy. But Hummel felt that the Christian students in the Y.U. program would be unlikely to take on Jewish rituals or seek to missionize to their classmates.

“It’s Yeshiva that’s hosting it, and so the power dynamics are a bit different than if it was Christian space,” Hummel said. “It would be a real uphill battle for a Christian to go into Yeshiva University and expect some type of big success with conversion.”

Institutionally, Yeshiva University is not expecting proselytizing to be an issue either. Ahead of the program’s launch, the university’s rabbinic leadership even issued a ruling that the program was permissible according to Jewish law.

“The Philos students also understand that themselves, that their purpose is to study and to learn about Judaism, that it’s not to try to convince or persuade,” Dauber said. “So that’s really not something that we’re worried about.”

Jews and Christians have studied together in religiously affiliated academic settings in the past. In 2018, Philos ran a leadership program for its Black members at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College, where they met with rabbis and African-American pastors to discuss Black and Jewish relations. That same year, David Nekrutman became the first Orthodox Jew to graduate from Oral Roberts University, an evangelical private university, with a masters degree in Christian studies.

The Y.U. program is different because students will undertake sustained enrollment at an Orthodox school.

“This is, in a lot of ways, an experiment,” said Robert Nicholson, president and founder of the Philos Project. “Can Christians and Orthodox Jews study together? Does it even work?”

He added, “Just the mere fact of forging a partnership with an Orthodox institution, to me, is a way of moving the ball down the field in Jewish-Christian relations.”

Hummel said that the partnership “isn’t just out of nowhere.” Modern Orthodox Jews and evangelical Christians also share what Hummel referred to as a “theological framework” around Zionism, which is understood as “a real covenant between God and the Jewish people that entails Jews being able to control their homeland.”

Talento, who came in not knowing the Hebrew alphabet, has enjoyed her classes so far. Learning to read biblical Hebrew is “something I couldn’t even imagine being able to do,” Talento said. Knowing Hebrew, she says, lets her “get more into the mindset of the author than you could reading a translated, English-language” text.

Later, she’ll be taking a class on the history of Judaism from the fall of the Second Temple through the Holocaust, and a class on Paul the Apostle, titled “Paul: Profile of a First-Century Jew.” It will be offered in the fall over Zoom and is open to any master’s degree student.

Talento, who has gone on a Passages trip to Israel, is not sure what she will do when she graduates from the program. She has worked for Passages in the past and has attended pro-Israel conferences held by advocacy organizations such as StandWithUs and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC. She is considering pursuing a career in the nonprofit world, working for Philos, or elsewhere in Israel advocacy.

“God only gives me the next step,” she said. “If you would have told me I was doing this a year ago, I would have said, ‘This is so cool — but I don’t even know how I was going to get there.’”