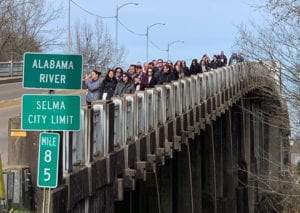

Members of the Young Leadership Cabinet of the Jewish Federations of North America cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama – scene of the 1965 Bloody Sunday confrontation between armed police and civil rights demonstrators – on a recent visit to civil rights historic sites in that state. (photo provided by Ben Vaughan)

Ben Vaughan didn’t need to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to know that civil rights remains a volatile issue in America.

The 36-year-old electrical engineer from Louisville is knee-deep in the struggle right here in Kentucky.

“I’m from the South, so I’m quite aware of the civil rights history in the South,” Vaughan said. “There’s a big push now within the Jewish community to talk about justice reform. [But] you can’t really talk about justice reform without talking about the civil rights movement and how so many things were left undone.”

In fact, Vaughan, a member of Jewish Community Relations Council, is personally involved in the fight to restore voting rights to hundreds of Kentuckians who have been unfairly purged from the rolls. More on that later.

Vaughan, a member of the National Young Leadership Cabinet of the Jewish Federations of North America, was in Alabama with 84 other Cabinet members from Jan. 31 to Feb. 3, immersing themselves in the history of the civil rights movement.

One of their visits was to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, scene of the Bloody Sunday confrontation between armed police and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr’s supporters on their historic Selma-to-Montgomery march in 1965.

“It’s a very small bridge,” Vaughan said, but with “unique aspects” and markers describing its place in history.

The group also visited civil rights institutions and landmarks in Birmingham and learned more about the Jewish role in the struggle.

That roll wasn’t always what it’s made out to be.

“It’s a complicated story,” Vaughan said. “The Jewish community in the South was actually split pretty much down the middle on the civil rights aspects. Some people didn’t want to deal with it; some people supported it. We were not the purveyors of civil rights justice that a lot of times we are held up to be. And a lot of that goes to don’t rock the boat.”

But Jews were targets, too.

On April 28, 1958, Temple Beth-El, in Birmingham almost became a scene of devastation when 54 sticks of dynamite were bundled in a canvas satchel in a basement window well outside the Conservative synagogue. The explosives never went off because the fuse had fizzled out.

That was only one of many attacks, or near attacks, on synagogues across the South.

The Beth El incident foreshadowed the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963 that killed four black girls.

The Cabinet members visited other sites and institutions dedicated to the movement, including the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, dedicated to the darkest chapter of the segregated South.

“From documents that they could gather from newspapers and public sources, they compiled a list of all the names of lynching victims that they knew of [from] all the states in the south – by county,” Vaughan said. “And they have actually carded those names into boxes that those counties could actually come and collect to put up a memorial.”

One of those victims was a Jew, Leo Frank, who was hanged in Georgia 1915, after being accused of murdering a girl in a pencil factory he owned.

“He’s the only acknowledged Jew [to have been lynched]” Vaughan said. “There are so many aspects to lynching that there’s so little information on. Of the thousands of names that they have, they don’t think it’s even 10 percent of the people who were actually lynched.”

Vaughan said the country has struggled with its “inability … to reconcile with civil rights issues and what we have done as far as slavery goes.”

He noted that other countries with catastrophic histories – Germany, Rwanda, Serbia, South Africa – have gone through some form of national reconciliation with their pasts.

“The U.S. has not reconciled with what it has done,” he said. “While civil rights were an advancement in the rights of people, it was not a statement of public acknowledgement of what actually happened.”

While the Cabinet itself does not take political positions, individual members get involved in justice reform, voter registration and perhaps more important, voter restoration.

Vaughan is involved with the Voter Registration Coalition on a constitutional amendment in Kentucky to restore voting rights to convicted felons who have served their sentences.

“There’s already significant voter disenfranchisement and voter suppression in our state,” Vaughan said. “There are currently 312 former felons who aren’t allowed to vote, and we’re talking about people who may have had a joint in the 1970s but have actually [committed] no violence. The things that people get felonies for and get disenfranchised is ridiculous.”