By Andrew Adler

Community Editor

It was two decades ago that – after generations of missteps and misstarts, pledges, projections and all manner of political maneuverings – the City of Louisville and Jefferson County reconciled their differences and became one entity: Metro Louisville.

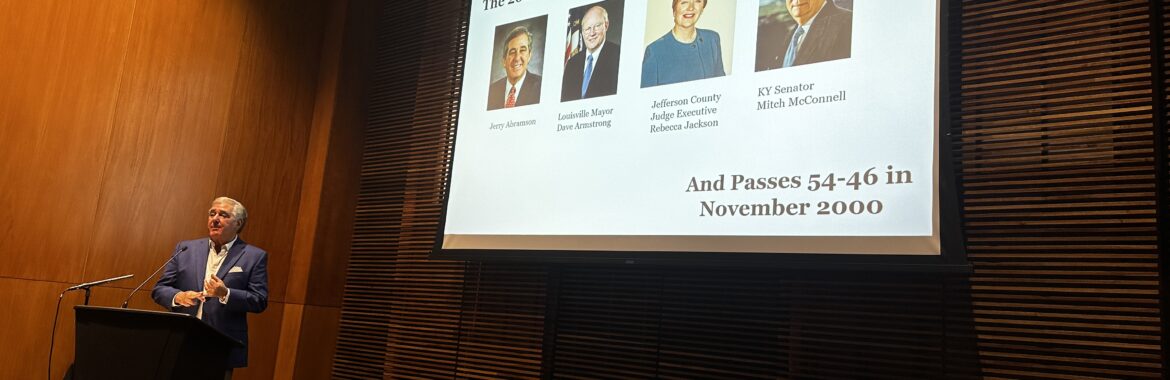

Jerry Abramson speaks at the Filson Historical Society July 21, 2023 about the 20th anniversary of City-County Merger (Photo by Andrew Adler)

Nobody was more responsible for merger’s eventual success than Jerry Abramson, who served five terms as Louisville’s first Jewish Mayor, garnering the admiring (usually, anyway) moniker of “Mayor for Life.” Earlier as a member of Louisville’s Board of Alderman (Metro Council post-merger) and afterward as Kentucky’s Lieutenant Governor under Steve Beshear, Abramson became the model of a savvy, pragmatic and unabashedly enthusiastic politician.

That enthusiasm was on full, unfettered display earlier this month, when Abramson reflected on 20 years of merger with an hour-long talk at the Filson Historical Society. The room was filled with friends and former colleagues, as well as anyone simply curious about what merger was all about, and how Mayor Jerry and his allies managed to pull it off.

It was something of a jolt to be reminded that merger first came up for a vote in 1956. That effort failed — as did subsequent initiatives in 1982 and 1983 – before finally succeeding in 2000. Merged government took effect on Jan. 1, 2003.

Abramson described the peculiar pre-merger establishment: a mayor and 12 Aldermen running the city; a Judge-Executive and three Fiscal Court commissioners (A, B and C Districts) administrating Jefferson County. In odd parallel were about 90 suburban “cities,” some as small as a few blocks. The city, with its large number of Black residents, was overwhelmingly Democratic; the county was predominantly White and Republican.

The resulting muddle sometimes bordered on the absurd. Abramson told, with a more than a hint of gleeful bemusement, how parking lot of McMahon shopping center in Hikes Point straddled, literally, the city-counter border.

“Half of it was in the county; half of it was in the city,” Abramson recalled. “So if you had an accident in the parking lot, you’d call 911, and they’d say, ‘City or County,” because they’d switch you, and then you’d say, ‘I’m in the parking lot of McMahon,’ and they’d say, ‘Are you on the East side or the West side?’ That was the exact reality we had to deal with at that time.”

Opposition to merger took many forms. Various constituencies feared their voting leverage would be diluted, that city and county police forces wouldn’t get along, or that because the city’s public-sector agencies were unionized and the county’s weren’t, chaos would ensue. Petty self-interest too often won out over the broader picture.

Most egregious from an economic perspective, divided government made it hugely difficult to convince new businesses to relocate to Louisville – or was that Jefferson County?

“The mayor and the city of Louisville would meet the decision-0maker at the airport, and I’d say, ‘Welcome to Louisville! Please locate within these 60 square miles.’ And the judge would say, ‘Welcome to Jefferson County! Please locate outside those 60 square miles.’ The next thing you’d know, he or she would get back on the plane and say, ‘Call me when you get your act together.’”

Circumstances improved significantly in 1985 with the signing of the City-County Compact, which created a framework that the competition to convince businesses to relocate. Meanwhile, the Kentucky legislature had passed a law forbidding Louisville and Jefferson County to ever completely combine, arguing that three bites at the merger apple was enough.

But an all-out blitz by Abramson and his allies succeeded in again putting the merger question before the General Assembly, and this time, they prevailed. And when merger was put on the ballot for the fourth time, in 2000, voters said yes.

A key strategy, Abramson explained, was transferring the task of drawing new, population-equitable districts away from politicians, and ceding it instead to the University of Louisville’s Department of Geography and Geosciences There, a team of graduate students helmed by Dr. David Imbroscio managed to accomplish what partisanship seldom could: design voting districts that didn’t leave traditionally marginalized constituencies – most notably Black voters – in the political wilderness.

“He did it, and did it perfectly,” Abramson said. “African-Americans were assured that (voting districts) would, at least, reflect the percentage at the time we had in the community, if not more so.”

Petty squabbles remained – one police department had stripes on its uniform pant legs and the other department’s didn’t. City police cars were white; county vehicles were blue (“so we got gray,” Abramson said).

“And the final thing I’ll say,” Abramson shared, “is the reason Louisville is called ‘Louisville-Jefferson County Metro Government.’ It’s not ‘Louisville Metro. Everybody says, ‘Louisville Metro,’ but nobody calls Indianapolis ‘Indianapolis Marion-County Unigov.’ Nobody says ‘Nashville=Davidson County Metro’ – they say ‘Nashville.’”

But “we were very concerned the first year that the county would think the city took them over. So rather than saying, ‘Welcome to the city of Louisville,’ we said, ‘Welcome to Louisville Metro.’ The reality – and I argue it and beat the drum to the media and everybody: It is, ‘The city of Louisville,’”

Jerry Abramson served as Mayor of Louisville from 1986-1999 and 2003-2011, and as Kentucky’s Lieutenant Governor from 2011-2014, resigning to become Deputy Assistant to the President and White House Director of Intergovernmental Affairs in the Obama administration. He left that post in 2017 and returned to his hometown of Louisville. Currently he is Executive-in-Residence at Spalding University, and a member of the University of Louisville Board of Trustees.