By Andrew Adler

Community Editor

The afternoon sun was blazing over Cave Hill Cemetery as the hearse, bright white, suitably immaculate, arrived at the gravesite. Cemetery officials opened the rear door, revealing a gleaming silver casket. Pallbearers bore the casket to its temporary resting place: a table erected under the welcome shade of a broad tent. Frien

Hosparus G-Force campers acted as pallbearers at the start of a mock funeral June 8, 2023 at Cave Hill Cemetery (Photo by Andrew Adler)

ds and relatives of the deceased sat quietly.

But this was no ordinary funeral. The casket was empty. The pallbearers and seated guests were children, ages 6 to 12. And during the service that followed, words of comfort came courtesy of Winnie-the-Pooh.

It was all part of a remarkable initiative organized by Hosparus Health of Louisville: G-Force, a four-day summer camp for children grappling with the remnants of personal grief. Each had experienced the recent death of a relative or loved one – perhaps a mother or father, sister or brother, grandmother or grandfather. Here profound sorrow was confronted, acknowledged, and the week progressed, hopefully diminished.

Camp T-shirts bore a declaration: Grief is a Force of Nature. So Are We.

This edition of G-Force unfolded during a week in early June. Successive days explored varying perspectives on coping with loss. Tuesday’s opening session took place at the Louisville Zoo, where campers learned how animals processed death. Wednesday unfolded at the Kentucky Science Center, taken up with the biology of dying. On Friday, campers let their bodies run free at the Trager Family JCC, followed by a closing ceremony at the nearby Hosparus campus.

The camp was organized by two Hosparus therapists: Joe Ferry and Erin Guthrie, who over these four days displayed a careful balance of empathy and practicality. Going to the zoo, for example, was in many respects a typical summer-camp excursion. Here, though, Ferry summoned memories of Helen, the matriarch of the zoo’s western lowland gorilla troupe, who died in October of last year at the age of 64.

“Then we started remembering other animals,” Ferry said, “like the mama giraffe who gave birth to a stillborn calf. And we thought, ‘Well. I wonder what animals do when they grieve?’ So we decided to spend the day learning about what animals do when they encounter death, and if we do anything like they do; what are the similarities and differences? Do they have feelings? Do they grieve in the same way we do? Do they handle death in the same way we do?”

Campers – who attend G-Force at no cost – were diverse in both background and specific experience. The one requirement is that the death of a loved one had to have occurred no more recently than two or three months, or more than two years ago

“Some are here because someone or several people they know who have died,” Ferry said. “Some are here for an unexpected loss, like the loss of a friend from an ATV accident. Some are here because of the death of a family member or a parent from an illness like cancer. Others are here because of a sudden loss of suicide or an overdose. We’re just here to learn about, what is thing called grief?”

On this zoo day, where laughter abounded, organizers had to carefully nudge them out of their comfort zones. “We’re purposely, sort of, stirring their grief a little bit when they are very self-regulated,” Ferry explained, “so they can learn without being in a highly aroused emotional state.”

Before boarding a bus to the zoo on the first day, the 40-odd campers gathered in a talk circle and broke off into buddy groups. “Everybody knows that everybody’s here because someone who has died,” Ferry said. “If we did nothing else, they have met 39 other kids who are going through something similar.”

The commonality of loss is a powerful engine.

“If you look around the room,” Guthrie said, “you can see them just smiling and laughing. And they’re talking and doing all these normal kid things. But they all know that they’re here because they also share that they’ve lost someone that they love. Even when we’re not talking about the people in our lives who have died, we’re processing and doing work with it. And kids do their work by play and exploration, so being able to use

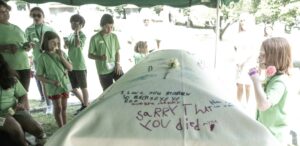

During a mock funeral at Cave Hill Cemetery June 8, 2023, Hosparus G-Force campers were invited to write messages of remembrance on a blanket that had been draped over a casket. (Photo by Andrew Adler)

the Science Center and the Zoo and the (Trager Family) JCC and of course, the cemetery — which is not your usual playground. But if you think about the idea that we learn by play, when we create a simulated funeral service, we’re learning by playing.”

Playing, and remembering, complete with a kind of communal eulogy. “Lifetimes are stories,” Celebrant Michael Higgs, manager of the Cave Hill Cemetery Foundation, told his young mourners, “each having a beginning, a middle and an end” no matter who it was that was lost.

“Let’s spend some time thinking about our stories about them,” Higgs said. “ ‘How lucky I am to have something that makes saying goodbye so hard.’ So said Winnie-the-Pooh when his friend, Christopher Robin, went off to school, and they had to say goodbye. What a great statement: It meant the life they shared was worth missing. It also means that the deep hurt of that loss is so hard, because the relationship mattered. And it still does.”

Helene Trager-Kusman leads Hosparus G-Force campers in stretching exercises June 9, 2023 at the Trager Family JCC (photo by Andrew Adler)

The next day, Friday – after a morning of stretching, basketball and much laughter at the Trager Family JCC – it was time for the G-Force to close out its collective experience. Speaking to his young campers, Ferry recalled how Hicks had referred to Cave Hill as “a sacred place,” not tied to any particular religion, but “a place of honor and respect.”

So too was the patch of ground where the campers, seated in a circle, were encouraged to quiet themselves and “simply reflect on our week,” Ferry said, and “remember the people we’re here to remember.” He played a song – “It’s OK” – written by 26-year-old Jane “Nightbirde” Marczewski, who performed it on “America’s Got Talent” in June of 2021 while disclosing she was grappling with terminal cancer. She died the following year, but not before “It’s OK” had become an international anthem of hope.

“We’re all a little lost sometimes,” Ferry told his campers. “It’s ok to grieve. It’s ok to feel bad; it’s ok not to feel bad. It’s ok to feel confused. It’s ok to feel angry. It’s ok to feel mixed up. It doesn’t matter. It’s all ok. And it’ll be all right.”

Ferry read aloud the names of those who had died. The children listened in silence. Some cried. Butterflies were released, fluttering up into the bright afternoon sky.

Parents, who’d remained at a distance while the closing ceremony moved forward, greeted their sons and daughters. Among them was Lynlee Kullman, reuniting with her eight-year-old daughter, Cameron. They’d lost her son and her brother, who’d died in an ATV accident when he was 11, just two months before.

G-Force Camp “was an incredible experience for her,” Kullman said. “She was able to process a lot and ask questions she wasn’t able to ask us in the moment when everything was occurring.” And “it helped me, because there were a lot of questions – things like funeral traditions, and cremation versus burial — that were hard for me to answer.”

Asked what camp had meant to her, Cameron, still in the present, answered simply, “It makes feel better. It makes me feel ok.”

Then mother scooped up daughter, each wrapping their arms around the other. It was a hug that affirmed that, even amid abiding grief, it would indeed be ok.

Lynlee Kullman embraces her 8-year-old daughter, Cameron, at the close of Hosparus G-Force grief camp Friday, June 9, 2023. Cameron’s older brother had died in an ATV accident two months earlier. (Photo by Andrew Adler)