By Andrew Adler

Community Editor

This is a story about life and loss, challenge and resilience. About channeling anguish into hope, exchanging the despair of illness and death into a declaration of enduring joy.

It is a story about Jerry and Sarah “Meghan” Steinberg, father and daughter, a parent with a child grappling with a cancer that would take her life at age 33. As the website meghansmountain.com tells it:

On January 29, 2005, Meghan, at the age of twenty-two, was diagnosed with leukemia (AML). At the time she was a student at the University of Louisville School of Justice Administration. Because of her illness, Meghan had to withdraw from school, give up her part time job, and begin the fight of her life – to climb a mountain against a disease that was known to kill.

In the early stages of her fight, Meghan realized that she nor her family truly understood what a cancer patient had to endure to beat this terrible disease. No one realized the emotional and financial toll cancer can take on a family. If they didn’t understand, then others must also not understand. For that reason, Meghan decided to open her world so that others could climb her mountain with her. She called her climb Meghan’s Mountain.

The Community newspaper wrote about Meghan in March of 2016, not long after her death on Jan. 23 of that year. Since then, Jerry Steinberg has continued to advocate for Meghan’s Mountain, the charitable foundation his daughter established to raise money and awareness on behalf of those affected by leukemia and related cancers. In 2023 he was among 13 recipients of a WLKY Spirit of Louisville Bell Award, given to area volunteers who “seek to inspire all residents to engage in community service.”

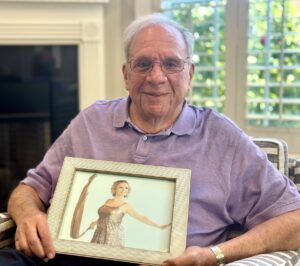

We caught up with Jerry Steinberg recently at his home in East Louisville. A retired attorney, he spoke about his daughter, their shared imperative, and the distinctive flavors of his current life.

“I’ve been blessed in a lot of ways,” Steinberg acknowledges, mentioning as an example his service on the board of the Louisville branch of Louisville’s Gilda’s Club. And for four years now, Meghan’s Mountain has sponsored a fundraising cruise on the Belle of Louisville, in which Gilda’s Club members are able to ride free of charge.

Initiatives like these help cancer patients gain more control over their lives, and a better sense of what brought them to their respective junctures. “Sometimes when you go through cancer, you forget a lot of the past,” Steinberg says.

Recalling his daughter’s journey after being initially diagnosed, Steinberg spoke of the immense challenges she had to confront. There was a four-month stay at Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, where she underwent a bone marrow stem cell transplant (the first of two) with her brother Justin as donor. There were remissions and recurrences, encouraging successes and sobering failures.

Along the way she asked a foundational question.

“Meghan walked in one day and said, ‘You know, Dad, none of us really understand cancer. We know that you can lose your hair, and we know that you can die, but do we know anything more about it?’ And I said, ‘You know, we don’t.’ And she said, ‘That’s because everyone is so damn scared of it that nobody’s interested in learning about it.’ So she decided she wanted to open up her world.”

Steinberg remembers the moment her leukemia diagnosis – made tentatively when she visited an urgent care facility for what she thought was a minor concern – was confirmed a few days later at Jewish Hospital.

“We were there and she just said to the doctor, ‘Well, whatever I need to have, let’s get it going, because I’m going to beat it.’ And she never wavered.”

His daughter may have been stoic about her cancer, but the reality of her disease shook Steinberg.

“I would stay at the hospital, and then go home to take a shower,” he recalls, “and I remember going down River Road and pulling over because it was raining so hard. But it wasn’t raining – I was crying. I was totally lost. I didn’t know what day it was.”

Back home, “I’d get on the computer and start looking up ‘leukemia,’” he said, “and I didn’t know what the hell I was reading. I didn’t know what I was doing, and all the while she’s putting it all together.”

It was then that Jerry Steinberg realized, anew, how much he needed the support of someone particularly close. “I remember – without making a phone call to him – at nighttime standing in front of Rabbi (Chester) Diamond’s house and ringing the doorbell.

“He had done her bat mitzvah, and he and I were very close,” Steinberg said. Diamond “opened the door, and I just started crying,” Steinberg said. “I could not stop. So, he took me in — and I will never forget this – he said, ‘Jerry, you’re not a doctor, and you’ll never be a doctor. You’ll never have the knowledge of a doctor. So instead of trying to read and understand things, ask questions – be an advocate for your daughter.’”

And there were certain profound limitations. “‘You’re not God,” Diamond said, so you can’t say, ‘My daughter is going to live, or not.’ But there’s something you can do that no doctor and no one in the whole world can do, except you.’ I said, ‘What’s that?’ He said, ‘You can define for her the word “Father.”’ I will tell you – I walked out of there and that changed everything.”

Meghan’s life became a whirlwind of physicians, hospitals, remissions, setbacks, determination, and the potential exhaustion. She forged an enduring connection to former U of L men’s basketball coach Denny Crum, spearheaded numerous fundraising events, and became a mentor to patients facing their own cancers.

“She tried to live a normal life,” her father said – she had hopes of becoming a nurse – but the ravages of her leukemia proved too debilitating.

By 2015, facing yet another round of treatments, Meghan decided enough was enough. “She said, ‘I’m not doing this anymore,’ Jerry Steinberg said. “She passed in January of 2016.”

Shortly before she died, Meghan – with characteristic calm determination – had planned much of her own memorial. “She said: ‘I know it’s going to be hard, but I need to talk to you about some things,’” her father recalled. “ ‘The first thing is about my funeral.’ She said, ‘I want to be buried next to my grandfather,’ who was my dad. ‘And I don’t want anybody wearing a coat and tie, because if they want to come, I want them to come with their heart, not with how they dress.’ And then she said, ‘I want you to continue the foundation.’”

That final request threw her father for a bit. “I looked at her and said, ‘Meghan, why would I want to keep it up? You’re not here; you’re gone.’ But that didn’t work. The foundation was never about me – it was always about other people.”

“Meghan was a girl who was way more mature than her age,” recalls Jerry Steinberg’s wife, Leslye Dicken. “Having passed at age 32, those many years battling cancer were handled with so much grace. She always cared about her “brothers and sisters” fighting cancer more than herself, even on her worst days. Meghan never met a stranger, making other people feel like family from the moment they met. Meghan inspired me to be a better person through her example.”

In the eight years since her death, Meghan’s Mountain has raised significant funds for Gilda’s Club, and made gifts to the Brown Cancer Center and similar recipients.

Jerry Steinberg had been a Jefferson County prosecutor before going into private law practice. At one point, tired and somewhat frustrated with how his profession was evolving, he took an extended break. “It’s a different world now, so it wasn’t as much fun,” he says. Indeed, once his daughter became sick, he never returned.

Steinberg remains close to Gilda’s Club — he sits on its board, and the facility has a special room named in honor of his daughter. He’s modest about being a Bell Award winner (“I was nominated by Gilda’s Club, which I thought they were crazy to do,” he says).

On the evening last year when he accepted his award, Steinberg acknowledged the defining, ever-present personality.

“I said, ‘You know, I probably wouldn’t have been here if it weren’t for Meghan. I think Meghan’s in this room, and I thank Meghan in front of everybody.’”