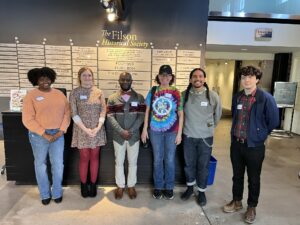

2023 Filson Community History Fellows (left to right): Mariel Gardner, Kat O’Dell, Donovan Taylor, Amy Shir, Marcos Morales and Nathan Viner (photo by Emma Bryan)

By Andrew Adler

Community Editor

About three years ago, Abby Glogower – Curator of Jewish Collections and Jewish Community Archives at the Filson Historical Society – approached the Jewish Heritage Fund with an intriguing proposal: to underwrite a program in which artists and scholars would pursue individual projects boasting strong local connections.

As the Filson itself explains: “The Filson’s Community History Fellowship brings together history advocates from diverse backgrounds and different parts of Louisville. Fellows meet regularly at the Filson to explore topics and tools in historical research, documentation, and interpretation. Fellows use these methods in real time by developing individual history projects of enduring value to their home communities.”

The first six-member cohort of these Community History Fellows spent April to October of 2022 pursuing their respective visions under the shadow of COVID-19. Pandemic realities brought inevitable compromises (more Zooming, fewer in-person gatherings) but the initiative proved conspicuously resilient.

No such restrictions have bedeviled the 2023 Fellows. And two of them – Amy Shir and Nathan Viner – are deeply enmeshed in the Jewish community, past and present. Shir is examining the legacy of the late activist Suzy Post (1933-2019), a former director of what’s now the ACLU of Kentucky, who devoted much of her life to the cause of social justice. Viner is exploring links between Jews and traditional Appalachian culture, particularly music.

Though they are a generation apart – Viner is 27; Shir is on the the cusp of turning 60 – both are anchored in the Jewish life of Louisville. She earned a B.A. in psychology from Wesleyan University and a master’s in public administration from Syracuse; he attended Eliahu Academy (Louisville’s Jewish Day School, which closed in 2008), and graduated from the University of Louisville with a B.A. in philosophy and the humanities.

Shir embarked on a career that, over four decades or so, has shifted from senior corporate finance to an emphasis on social justice – a natural adjunct to Post’s own points of emphasis. Viner landed an internship at the Criterion Channel, renowned for its collection of classic films, soon afterward gaining a full-time position as a programming coordinator.

“I get a lot of energy from this group,” Shir says. “They’re young; they’re creatives. They’re all working on very different projects. And they care about each other. We promote each other and show up at each other’s events. I don’t know if I would ever have known these people if Abby hadn’t had this cohort.”

“We wanted to bring together people from different backgrounds who were interested in history work that found meaningful to them as individuals, and to their communities,” Glogower explains.

Initially, “we thought about starting the program with just an open call: ‘Apply to be a Community History Fellow.’” she says. “But we were worried that if we did that, we wouldn’t end up with enough true diversity. So we’ve been working directly through outreach with community partners, within networks, and asking friends and (others) to recommend people to us. Then we’ve been approaching these people and saying, ‘Tell us about a project you want to work on, and would this be a good fit for you?”

As a ground-zero strategy, being proactive has paid off. “It’s been a little more like recruitment,” Glogower says. “The idea is that, if the program keeps going, it will grow into more like an open application process.”

For Viner, good intentions and good luck aligned in his favor. “It was very serendipitous when I came to Abby, because I’d been chewing on thoughts about Jewish artists who focused on the South.”

He’d spent a week at the Cowan Creek Mountain Music School in Whitesburg, Ky (a city best known as the home of Appalshop). “They kept naming all these different recordings, or players and books about the music, and it was just like, ‘John Cohen,’ ‘Art Rosenbaum’ – and I’m thinking, ‘What’s happening?’ That’s what my project is all about?

Cohen is a fascinating personality. Born in 1933, he was founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers, while making a name for himself as a musicologist photographer documenting folk musicians in Appalachia. He gained attention for his 1963 film The High Lonesome Sound, demonstrating unusual sensitivity toward the plight of local residents, many of whom were mired in poverty. He died in 2019 at the age of 87.

“I’m going to screen it at the Speed (Art Museum) Cinema on October 8,” Viner says. “I’m going to get a 16mm print of the film from Indiana University, which is the real thing, a beautiful black-and-white, 30-minute documentary.

For Viner, encountering Cohen’s works was akin to an expressive thunderclap. “I got his photography book – there’s not much writing in it. He doesn’t talk too much about being Jewish. There’s a little paragraph where he talks about being a kid in New York City who went to shul with his grandfather, who was Orthodox.”

Now, “I know so much about John Cohen,” Viner says. “I know how people from the area felt about him recording him, because I’ve been there and asked them.”

Viner had the makings of a project – a first step.

“So I started refining it, trying to figure it out,” Viner recalls. One especially useful action was connecting with Nathan Salsburg (“a Jewish kid!” Viner exclaims), a Louisville-based folk guitarist who curates a digital archive devoted to Alan Lomax, the ethnomusicologist who spent much of his career making field recordings of 20th-century folk musicians.

“Eventually I came to Abby to hear her thoughts about what was possible,” Viner says. “That’s when she said, ‘Well, there’s an opening in this program, if you have any interest.’” Such a collaboration made perfect sense. “Because I have a background in film curation,” Viner observes, “it was coalescing into, probably, a film program.”

His proposal quickly hooked Glogower, the daughter of a modern orthodox Michigan rabbi who came to the Filson in 2017 after earning a Ph.D in Visual and Cultural Studies from the University of Rochester.

As she learned more about Viner’s intentions, her interest gave way to a kind of giddy anticipation. “In my mind I’m like, ‘Nathan, I’m obsessed with your project. Please do this – please do this,’” Glogower says. “Because, heck, I’m not from here; I don’t know anything about banjo music. I feel like an outsider, so I want to learn about this.”

Shir’s route to the Filson was more circuitous. “I’m a ‘boomeranger,’” the Louisville native quips, “having grown up in this Jewish community and having left for places like New York and Berkeley and Atlanta, and then coming back. I brought a lot of progressive social justice activism with me that I picked up everywhere I lived. So Suzy Post was a real mentor to me when I moved back and ran for state representative in 2006.”

Though Shir’s run was unsuccessful, the experience reinforced her belief in personal and professional opportunity, particularly via shared imperatives. “We stand on each other’s shoulders,” she says. “Now Karen Berg is a state senator, and we have (state representative) Tina Bojanowski and (former state representative) Maria Sorolis, so Democratic women are winning out there.”

Meanwhile, Shir had met Post and soon realized they were in sync. “Suzy and I just formed a bond. Like Suzy, I’ve always been interested in the broader community here and the injustices of our segregated city…so when she passed away in early 2019, I realized that here was someone who meant so much to me and a lot of my peers, but that there are a lot of young Jews who don’t know Suzy.

“My project is making sure that young Jews know the legacy of Suzy Post,” Shir says. “That they understand desegregation and women’s rights and Title Nine, how she was part of the underground railroad that sheltered folks who didn’t want to serve in the Vietnam war — and that she was the first executive director of the Metropolitan Housing Coalition tackling affordable housing, which is still a persistent problem here.”

To those ends, Shir will meet with young Jewish adults at the Trager Family JCC Sept. 7 from 6:30-8 p.m., (RSVP to Bridget Bard at bbard@jewishlouisville.org) and will visit classes at Louisville’s High School for Jewish Studies on Oct. 22. The idea, she says, is to use Post “as a prompt (about) the issues she dealt with and what she did about them, and then having young Jewish adults break off into small groups and have conversations about what’s meaningful to you, and how might pursue activism on those issues.”

Like Shir, Viner’s relationship to his native city is complex and deeply personal. His project amounts to “a reckoning with the identity of being a Jewish person from Louisville, Kentucky – being Jewish here as part of a southern city, but also part of a diasporic community that’s constantly in conflict with assimilation.”

Community History Fellows are, by design, ambassadors as well as creators.

“The whole point of the program is also to build relationships, and pipelines,” Glogower says, particularly in predominantly Black areas of Louisville. “Historically, museums, historical societies and cultural institutions, have a bit of a diversity-pipeline problem.” Both the 2022 and 2023 CHF cohorts have not only acknowledged diversity – they’ve embraced it as a core value. It’s one reason why the program gained vital support in the first place.

“I’m really grateful to JHF for taking a chance on this idea,” Glogower says. “Because normally, grant projects seek to be very quantitative – ‘We’re going to get this many people in chairs for this lecture’ – I basically came to them and I was, like, ‘I need a lot of money to do very slow work with a small number of people. And I want to pay them money, and I want to feed them. So it was a very different kind of thing. But I felt in my heart, what’s there to lose in trying. And they took a chance on this program, which was such an honor.”

The JHF committed initially to fund two cohorts of Community History Fellows. “We do have to figure out how to make it sustainable,” Glogower acknowledges, “because my colleague, Emma Bryan (the Filson’s Community Engagement Specialist) are doing this on top of our other jobs at the Filson. So we’re in the process of trying to gather feedback from the Fellows. We’re listening and learning, because I do want to keep it going.”

Besides Amy Shir and Nathan Viner, the 2023 cohort of Filson Community History Fellows comprises Mariel Gardner, Marcos Morales, Kat O’Dell and Donovan Taylor. You can learn about them and their projects at https://tinyurl.com/544nm2h8