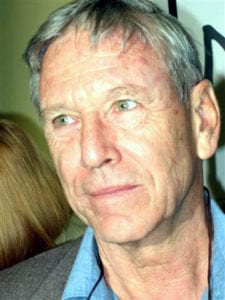

For so many, the loss of Amos Oz at the very end of last year came as an unbearable blow. It is hard to imagine Israel without his prophetic voice and his poetic prose.

His novels, short stories and essays form an essential window into the country’s soul, portraying the crucible of its birth, its tempestuous political landscape, and indelible impressions of Jerusalem (achingly beautiful yet pervasively melancholy).

Oz also captured the triumphs and shortcomings of kibbutz life. As a young kibbutznik in the 1970s, I discovered through his characters (in novels like A Perfect Peace and stories like Nomad and Viper) that, though humanity’s greatest ideals were at the heart of the kibbutz movement, no matter how noble the vision, human frailties and imperfections would always blemish utopian aspiration.

As is familiar to readers of his greatest masterpiece, A Tale of Love and Darkness, Oz fled his childhood home in the aftermath of his mother’s suicide and began a new life at Kibbutz Hulda (changing his name from Klausner to Oz, Hebrew for bravery and strength), and began publishing stories while working in the cotton fields. In spite of many years spent living in the desert development town of Arad and later Tel Aviv, it seems revealing that it was the kibbutz of Oz’s youth where he wished to be buried.

A combat veteran of the 1967 and 1973 wars, Oz was above all an ardent warrior for peace. As early as 1967, at age 28, he wrote passionately in Davar against the occupation of the newly conquered Palestinian territories, warning of the dangers of “expansion and eternal annexation.”

Not surprisingly, he became a founder of Peace Now and remained a steadfast champion of the two-state solution. For that, he was sometimes denounced as a traitor and even threatened by rightwing Israelis.

At his memorial, Oz’s childhood friend, President Reuven Rivlin, concluded his eulogy by addressing the iconic writer’s brave stand against the rightwing establishment: “Not only were you not afraid to be in the minority and hold a minority opinion, but you weren’t even afraid to be called a traitor. On the contrary, you saw the word as a title with honor.”

Fittingly, in his final and perhaps most universal novel, Judas, Oz immerses readers in a brilliantly imaginative meditation on what it means to be called a traitor and the fraught relationship between nationalism and critical citizenship, competing versions of what the Israeli state should aspire to be.

No appreciation of Oz’s life and legacy could match the eloquence of his own voice, so it seems apt to conclude this reflection with a brief passage from his final book, a slim essay collection titled Dear Zealots, which, as much as anything he ever penned, glows with humanity, humility and moral clarity.

“Contending with fanaticism does not mean destroying all fanatics but rather cautiously handling the little fanatic who hides, more or less, inside each of our souls,” Oz wrote. “It also means ridiculing, just a little, our own convictions; being curious; and trying to take a peek, from time to time, not only through our neighbor’s window but, more important, at the reality viewed from that window, which will necessarily be different from the one seen through our own.”

Such wisdom clearly speaks to our own deeply polarized country.

(Ranen Omer-Sherman is the Jewish studies chair at the University of Louisville.)