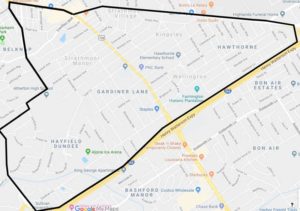

The Highlands Eruv stretches from the Watterson Expressway to Douglass Loop – a perimeter of six miles – and connects with the Anshei Sfard Dutchmans Lane Eruv. (Map provided by Rabbi Simcha Snaid)

By Lee Chottiner

Community Editor

Snaking more than six miles through the Upper Highlands and other neighborhoods hugging the Watterson Expressway, a series of 238 PVC pipes attached to utility poles, plus a highway wall, are making it easier for Louisville’s only Orthodox Jewish congregation to attract new members.

It’s the city’s new Highlands Eruv, a symbolic extension of kosher households that enables Orthodox families to walk to and from synagogue, and each other’s homes, carrying books or pushing strollers or wheelchairs, without violating the work prohibition on Shabbat.

The eruv, which was completed three weeks ago, is an essential piece of infrastructure if Congregation Anshei Sfard is to grow, according to its rabbi, Simcha Snaid.

In fact, one of the first questions he gets from younger families interested in relocating to Louisville is whether there is an eruv surrounding the neighborhoods where they would likely buy or rent a house.

“We wanted to make sure that it was built, not just for the families that are already here, but to recruit and build a bigger community,” Snaid said. “This amenity was needed to make sure that’s an option.”

Another eruv already exists along Dutchmans Lane and is still enforced and is connected to the new one.

But that’s not where Anshei Sfard, which sold its old building to the Jewish Community Center in 2019 for the new JCC campus, plans to locate its next synagogue.

The 38-family congregation expects the future building to be somewhere within the confines of the new eruv, which includes Hayfield-Dundee, Gardiner Lane, Strathmoor Manor and Village, Wellington, Hawthorne, Kingsley and part of Belknap. It stretches to Douglass Loop even touches Newburg Road.

Six to seven AS families, including Snaid’s, already live in the area where the synagogue will be.

“We’re trying to find a location for it,” Snaid said. “We’re always looking for something to rent, something to buy, an open area where we could build something. All options are on the table.”

The eruv took four to five weeks to construct scattered over a much longer time period because Snaid’s partner in constructing the barrier, a Chicago rabbi, needed to fit it into his schedule.

Enter Rabbi Mordechai Paretzky of the National Eruv Initiative, a specialist in eruv construction worked with Snaid to put up the eruv.

“It’s actually unusual for the rabbi to get his hands dirty and do the physical work,” Paretzky said of the project. “But it also happens to be of tremendous benefit. He (Snaid) knows every component in the eruv. He knows how the eruv was constructed literally, so when issues arise, he’s much better equipped to handle it.”

Paretzky has helped construct approximately 15 eruvs around the country.

“It is specialized work. You need to have lot of knowledge of Jewish law and practical creativity to put something like this together.”

This particular eruv is less than average in size, Paretzky said. Still, it proved “extremely difficult” to put up because most of route, except the Watterson portion, did not include walls or fences that could be incorporated.

That left Paretzky and Snaid with no option but to attach 10-foot-long PVC pipes on LG&E utility poles, making symbolic doorposts called lechis.

Fortunately, Paretzky, being a mayven of eruv assembly, has an essential piece of equipment for the job – a bucket truck.

Getting the materials for the eruv caused a delay. Not surprisingly, one can’t just walk into a hardware store and expect to find 238 PVC pipes, one inch in diameter and 10 feet long.

“We ordered a huge shipment because in the store itself they didn’t have that amount,” Snaid said. “So, they had to order it, and they put it in my backyard with a forklift – pipes, brackets, everything.”

Anshei Sfard is renting space on the utility poles from LG&E.

The work won’t now that the eruv is built. Snaid inspects it once a week, taking 30-to-60-minute drive along the entire perimeter to make sure it is intact. He said an errant tree branch or a LG&E crew doing maintenance work could jar a line or pipe out of place, rendering the eruv unkosher.

He didn’t disclose the cost of materials and Paretzky’s service, but he said the whole process was worth it.

“It is a costly endeavor, but it is needed to build an Orthodox Jewish community.”

Build it and they will come