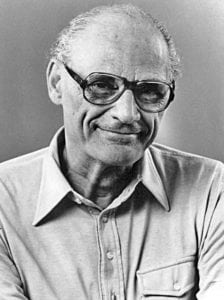

Arthur Miller: Writer, a lovingly crafted documentary about the award-winning playwright set to air on HBO , doesn’t reveal a lot of new information. A good portion of the film involves Miller himself speaking from the audio version of his 1987 memoir, Timebends: A Life. And much has already been written elsewhere about the tumultuous life of the Jewish author who gave us classics such as Death of a Salesman and The Crucible, and spent much of the 1950s in the public eye.

But the film succeeds at filling the gaps between Miller’s public and private lives, painting a fuller and more nuanced portrait of one of the 20th century’s most celebrated writers. That’s probably in large part because the film’s director is Rebecca Miller, Arthur’s daughter.

The movie, which premieres March 19, is as much a warm and intimate father-daughter conversation as it is a summary of his life. It traces Miller’s story from his childhood in New York City to his marriage to Marilyn Monroe to his run-in with the notorious “anti-Communist” House Un-American Activities Committee.

But the film also captures Miller in unguarded moments, in his woodworking shop and in his garden with his third wife, Inge Morath, who was Rebecca’s mom and a noted photographer. Rebecca follows him through these moments, asking questions that search for the secrets behind his creative process.

In a phone conversation, Rebecca Miller told JTA that though she wanted to be a filmmaker growing up, her sessions with her father, which began over two decades ago, started as more of a family project than a potential film. (These days, she is a respected indie filmmaker and author, and is married to the Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day-Lewis.)

“In the beginning, I just wanted to get the stories down,” she said.

In film school, though, Rebecca Miller won a prize for an unrelated project and was given reels of professional-grade 16 millimeter film. That made her “think of doing more formal interviews and turning it into a more serious film.”

Rebecca eventually found a treasure trove of old family films dating back to the 1940s and added interviews with her two half-siblings, Robert and Jane (born to Miller’s first wife, Mary Slattery); Arthur’s older brother, Kermit, and his younger sister, Joan Copeland; as well as with Jewish playwright Tony Kushner and the late Jewish director Mike Nichols.

On its own, Arthur Miller’s story has enough ups and downs to pack far more than the film’s 98 minutes. A lackluster student, Miller took a job after high school that required a 90-minute commute. He began reading what he called “thick books” on his way to work that awakened literary ambitions. At the University of Michigan, Miller twice won the school’s prestigious Hopwood Award for creative writing. While there, he met and married Slattery, a lapsed Catholic.

“She wanted an intellectual and Jewish artist, and I wanted America,” Miller says in the film.

The newly married Millers moved to New York, where his first Broadway effort, The Man Who Had All the Luck, had none, closing after six performances. Miller’s fortunes changed in 1947 with the debut of All My Sons, his initial collaboration with director Elia Kazan. The play, which involved a company that knowingly manufactured defective airplane engines, won multiple Tony Awards.

Miller followed that with Death of a Salesman, which debuted in 1949 and is widely considered one of the great American plays of the last century. The protagonist Willy Loman was based on one of the playwright’s uncles.

“There is an ongoing debate on how Jewish the Lomans are,” Rebecca said. “They’re Jewish if you want them to be Jewish. Certainly they were based on his own family.”

Asked in the documentary if he was Jewish, Miller responds, “Absolutely Jewish. But I inherited from my father the attitude of being American more than being a Jew.”

That was typical of his generation of American Jews, who hoped to assimilate, Rebecca noted. But she also said she had heard Miller’s great-grandfather was a rabbi. His mother kept kosher at home until she developed a “taste for bacon.” In one of their last conversations in the film, Miller says a play “is the process of approaching the unwitting, the unspoken and the unspeakable.” Rebecca suggests that that sounds a lot like Kabbalah, and he agrees.

At the height of the McCarthy era, Miller penned “The Crucible,” a thinly veiled indictment of the House Un-American Activities Committee, using the Salem witch trials as backdrop. (The committee later found him guilty of contempt of Congress when he refused to out fellow artists as communists. He received a suspended prison sentence and was fined $500.) In 1956, he married Marilyn Monroe, who converted to Judaism. They divorced in 1961, and Monroe died of an overdose little over a year later.

Three years after Monroe’s death, Miller reunited with Kazan for After The Fall, a roman a clef that re-created his life with Monroe. It was savaged by reviewers. When talking about the play in the film, Miller laments the future of playwriting and his treatment at the hands of critics.

Miller never enjoyed superstar success again. Among his subsequent plays were Incident at Vichy (1964), about a group of men detained by Nazis; The Price (1968), which featured Gregory Solomon, a Yiddish-accented character; and Broken Glass (1994), about a Jewish couple from Brooklyn set around the time of Kristallnacht.

In the film, Rebecca is able to bring out a warmth and honesty from her father — he was hardened by public scrutiny and decades of waning critical relevance — that a stranger might not have elicited. The viewer can hear her say things such as “OK, Pops, you’re on” while filming.“

[His] public persona is so different from the man I knew,” she said. “I felt I was the only filmmaker he would let close enough.”

“Arthur Miller: Writer” debuts at 8 p.m. March 19 on HBO.