By Andrew Adler

Community Editor

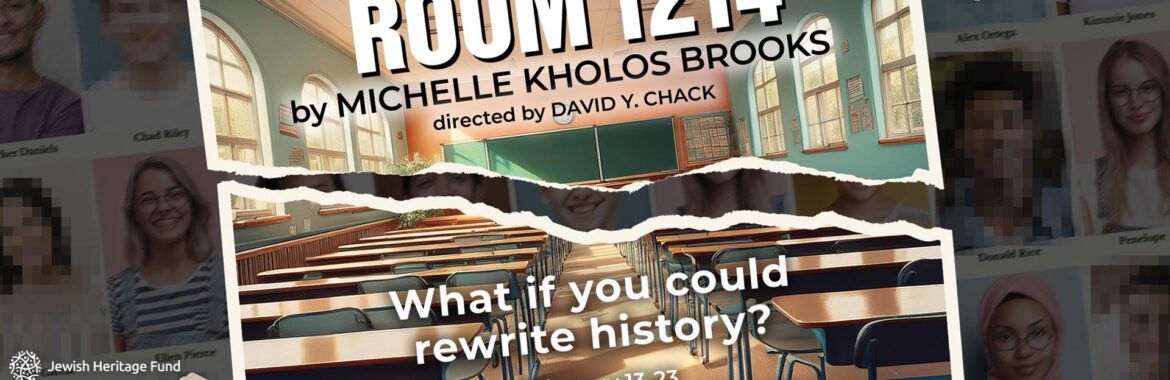

Michelle Kholos Brooks’ drama “Room 1214” comes to the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts Feb. 13-23.

It was a spasm of carnage all too familiar amid the annals of American gun violence: a teenager brandishing an assault rifle strides into a school, opens fire and within minutes renders a place of quiet study into a scene of unfathomable horror.

So it was on the afternoon of February 14, 2018 —- Valentine’s Day — when a 19-year-old former student returned to Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., shooting 17 people to death while wounding 17 others. That was terrible enough.

Yet somehow even more terrible – as if that were even possible – was that several victims were gunned down as they sat in a classroom learning about the Holocaust. Out of that supreme irony emerged Room 1214, playwright Michelle Kholos Brooks’ self-imposed imperative to make sense out of what can only be called senselessness.

The play, which had its premiere in 2024 in a staging by the New York City-based New Light Theater Project, is coming to Louisville for performances Feb. 13-23 at the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts. It will mark the second collaboration between Brooks and Louisvillian David Chack’s ShPIel Performing Identity theater company, which two years ago produced Brooks’ H*itler’s Tasters – another example of history reconsidered through the lens of audacious imagination.

Yet where H*tler’s Tasters is rooted in events from the There and Then, Room 1214 is unmistakably a product of the Here and Now. Brooks based her memory drama on a series of conversations with history teacher Ivy Schamis, who on that February afternoon was guiding her students along the terrible byways of the Shoah. Two of those students perished after the gunman began firing into her classroom.

When she learned about what had occurred, Brooks almost immediately recognized the potential for creating a potent act of theater. For her, it was an inevitable declaration of expressive intent.

“There’s something in me that connects to these very specific stories,” she explained during a recent Zoom interview from her Southern California home, “when I’m crossing paths with something I feel I need to point out or pay attention to. What happens is that I land on a story, and I go: ‘Wait – what?’ Hitler had used young German women to taste his food for poison; or ‘Wait – what?’ – this woman was teaching a Holocaust history class when this 19-year-old kid shot into her classroom with swastikas on his bullets and his boots.”

Room 1214 posits an intriguing scenario: What if that teacher could return to her classroom and revisit that awful day, but with the murdered students restored to life? How would she channel the collective energy around her? Would it make any difference that the school itself, bound up in the misery of recollection, was about to demolish the area that housed the classroom?

The immediacy – the proximity of history — was itself the point. And in many respects, it reflected Brooks’ foundational imperative as a writer: How can a playwright take the germ of an event and apply a kind of creative alchemy, rendering fact into fiction and ultimately, into a declaration of essential truth?

“I think I’m – and this is one of my fatal flaws – a very, very impulsive writer. I don’t think about a whole lot before I start. I just dive in, and a lot gets revealed to me. Once my fingers hit the keyboard, that seems to be the conduit for me.

So it was when Brooks was done writing Room 1214.

“I remember where I was, and I remember sort of sweating, and I remember how I felt when I was finished,” she recalls. “I looked at it and said, ‘Okay, I did it.’ But I said, ‘No one’s ever going to produce this play. There’s no way anybody is going to want to touch this play, because it’s very confrontational.”

Momentum, however, ended up being on her side.

“We don’t have a lot of time for these stories to simmer for 10 years down the road,” Brooks says. “This is a critical issue for our society. Anybody who thinks their lives will not be affected by gun violence at some point is delusional.”

Indeed, “all the young people I know – the first thing they do when they walk into a classroom is look for the chair where they’re least likely to get shot. They look for exits. They think about movie theaters before they go into them. I do it, too. It colors everything we do.”

Even so, “I don’t think there’s any time to wait and wonder if we’re doing the right thing,” Brooks acknowledges, “or if we’re doing enough.”

And what are audiences to make of this potentially unsettling play?

“I wonder if I could throw in something Michelle said to me the other day,” Chack says. “This is raw, so intense, that it kind of stops them from immediately wanting to come see it.”

Compare that to works about the Holocaust “that are rising up everywhere, selling out. People are going to plays and performances about the Holocaust – why is that? Why is that something people will turn out for, but (not) they’re seeing massacres happening on our own soil. What is so off-putting I can’t see that – but it’s easier to go to a performance about genocide of six million Jews.”

Perhaps it’s a function of how historical distance tends, even subconsciously, to insulate us from that aforementioned rawness. The Holocaust unfolded 80-some-odd years ago, and time has a way of rendering its own kind of judgement.

“People cry; people feel self-satisfied about what they attended,” Chack says, “yet there are horrible things happening right now in America. That’s what Michelle’s play does.” Not surprisingly, the core follow-up question, Chack says, is “what are we doing to apply those lessons to what’s happening today? And why can’t we see theater and performance that exposes that?”

On this subject Brooks is unapologetically didactic. She’s sick and tired of rampant mass shootings in America, and wants you to be sick and tired, too.

“What I said to people in New York, where we just did 1214, if we can get just one person at every show who wants to do something – who’ll write to their congressperson, who’ll donate some money, who will march – then maybe we’ll have done something besides just talk about how horrible it is, and then move on. Until it becomes our kid or our parent or our synagogue or our community.”

***

In conjunction with the Kentucky Center’s upcoming production of Room 1214, the Jewish Community Relations Council will host a post-performance panel discussion on Feb. 16. JCRC director Trent Spoolstra remarked:

It is a true pleasure to partner with David Chack on a panel discussion for Room 1214. This play touches on so many topics that are at the forefront in today’s society including the Jewish community: the tragedy of school shootings, the need for continued Holocaust education, and recovering from the trauma of violence. Our Jewish Community Relations Council has a responsibility to partner with those across our city to help bring awareness and tackle key social issues that continue to afflict our world. I look forward to sitting on a panel with key community leaders after the show on February 16 to discuss these issues and what we can do together to make our communities safer.

Room 1214 runs Feb. 13-23 at the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts’ MeX Theater. For tickets, go online at https://tinyurl.com/42s7nfsh