Rothschilds share recollections of their ordeal during WWII

[by Cynthia Canada]

On March 25, 2013, the Louisville Courier Journal published an article by Peter Smith, telling the story of John and Renée Rothschild’s escape from German-occupied France in 1942. It is a riveting adventure, a fairy-tale romance, and a deeply personal view of world history.

On a recent Sunday morning, the Rothschilds and I found a rare quiet corner at the Jewish Community Center and spent more than an hour talking about that story and the times before and since.

They met at harvest time in 1939. John and his immediate family were Swiss citizens, but his mother owned a farm, St. Radegonde, near Saumur, France, where they lived with extended family. Renée’s parents had sent her to Strasbourg, France, where they hoped she would be safe from the turbulence back home in Germany. When Strasbourg was evacuated and Renée was stranded in Saumur by a train derailment, she called a friend – John’s cousin – who invited her to stay the night. John’s mother asked her to stay on and help with the harvest, and within three weeks, John and Renée were talking of marriage.

John’s mother, sensible lady that she was, insisted that her son finish his Swiss military obligation and find a job before taking on a wife and family. Renée stayed for five months, then moved to Paris to live with family and work; John returned to Switzerland.

There was some tension when the Germans invaded France, but the military occupation proved relatively uneventful. However, with the invasion of Russia in 1941, the Gestapo moved into France, bringing grave danger. But it was not until 1942, when the Vichy government secretly agreed to let the Germans deport all foreign Jews, that the situation hit home.

John’s family was arrested in July, 1942. The Gestapo confiscated their Swiss passports and everyone there – grandparents, parents, children and friends – were sent first to a holding camp and then to Auschwitz. Renée was arrested in August. She asked one of the French police officers present to send John a telegram telling him where they were taking her; thankfully, the policeman complied.

From that point, a series of helpful gestures bolstered John’s quick action to locate Renée and obtain her release. His employer advanced him a month’s salary to make the trip to Rivesaltes, where Renée was being held; old acquaintances offered help in the way of favors he could call in. He was able to delay Renée’s departure for Auschwitz, and ultimately to get her out of the camp – but without the proper papers to go back with him to Switzerland. After a month’s delay, they finally crossed the border at a clandestine location, late at night, with the aid of guides hired by a Jewish storekeeper in a town on the French-Swiss border.

The way John tells the story, with energy and dash, I can understand the emotion behind Renée’s exclamation: “When I saw he had come for me, I knew he was my knight in white armor!” But fairy tales are never exactly what they seem on the surface, and I wondered what happened after the “happily ever after.”

As it turned out, what happened immediately was surprisingly down-to-earth, at least to me. (Of course, I’m not Swiss – and the Swiss do have the reputation of being pragmatic to a fault.) After resting the night at a hotel, John called his office. They were delighted to hear from him, since they really hadn’t expected he would make it back safely – particularly with Renée. John got his old job back on the spot; he and Renée were married shortly thereafter and moved into John’s apartment. Renée got a job, and they worked. They started a family, they moved to the U.S., and they decided to stay.

I wanted to know what job Renée found. “I worked for the Red Cross,” she told me. “I helped people who were trying to find their relatives who had disappeared in the war.”

“That must have been hard,” I said, thinking of Renée’s and John’s families and imagining the anguish of knowing what might have happened – what probably had happened, based on what Renée was finding out about other people’s relatives – and being able to do nothing.

Renée nodded. “Yes,” she said. “It was hard.” It was the only moment I saw her look sad –and it was only a moment.

“After after being in the camp, not knowing what would happen or whether you were going to be able to get out, was it difficult to feel safe again?” I couldn’t imagine otherwise, but Renée surprised me.

“Oh, no,” she said emphatically. “I stayed busy. I didn’t sit around the camp worrying about what would happen. I took stenography, I translated for people. There were so many of them, and I knew some of their languages – there was work for me to do. I got in touch with the Red Cross and we got milk for the little children. It was an important thing, getting milk for the children – I didn’t have time to be afraid.”

I made up my mind to remember those words and the philosophy behind them as closely as I can for as long as I can. When it seems life could be over tomorrow, find something useful to do. If time really is that short, there’s none to be wasted sitting around being afraid.

Still, I wondered, wasn’t it a tough adjustment, going from small towns and physical labor to big cities and professional employment – from rural France to, ultimately, corporate America?

John shrugged a little and said simply, “We have each other. We have a beautiful family. We have made a good life.”

Up to now, John had been telling most of the stories, with Renée interjecting occasionally. When we started talking about family, though, she got busy, opening folders and passing pictures, articles, maps – all sorts of illustrations for story after family story. And when it came to the pictures, she told many of the stories.

There were several pictures in the folder of Renée’s family – her parents, her younger sister Martl, and a cousin, Margot (who now lives in New York). Her father, Heinrich, was injured in World War I while carrying wounded soldiers from the front lines to receive medical care. The pictures of Heinrich Bodenheimer show a mischievous looking man with a moustache and a cane; I looked at him smiling out of the pictures, and I had to smile back. Her mother, Elsa, looks grounded, sensible, more reserved.

The daughters, Renée and Martl, are sweet children, dressed in costumes – Renée in a tall hat and dress with pom-poms, like a clown suit I used to have, and her little sister with flowers in her hair. Martl, in particular, has a toddler’s impish gleam. As teenagers, they look much like their mother.

In 1941, John sought out Renée’s family. Her mother and sister had been deported from Kehl, and her father, who had been in Switzerland at the time, had been detained when he went to find them. Renée had to stay in the free zone; it was too dangerous for her, as a foreign Jew, to travel south into German-occupied territory. John, as a Swiss citizen, had protection at that time, so he went alone.

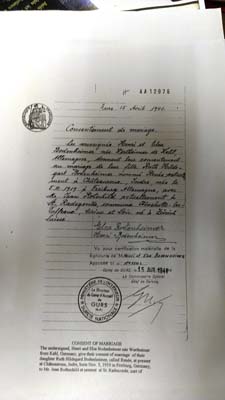

He found the Bodenheimers in a holding camp at Gurs, near the Spanish border. They visited, and he told them his intention to marry their daughter. Heinrich – “This is the kind of man he was!” John exclaimed – found paper and pen, and in his beautiful handwriting, wrote a document officially granting permission for the marriage. He and Elsa signed it, they had it witnessed, and then, “He found a bottle of wine so we could celebrate.”

It was the last visit for any of them. Heinrich, Elsa, and Martl were later shipped to Auschwitz, where they were killed. At the time of her death, Martl was 19 years old.

At the farm, life was more tranquil. The military occupation seemed non-threatening; the Rothschild family responded to a call from German troops to board draft horses and received a visit from officers who inspected their stables to make sure they were up to standard. It was a simple business call.

A few days later, in town, two young German soldiers recognized John and his brother and stopped to chat. After a while, they asked if they could come out and visit. “What could we say?” John told me. “They were German soldiers – but they were nice fellows. So we told them yes.”

The two visited the farm often during the occupation. On the first visit, they wanted to know if the Rothschilds listened to the war news from Great Britain, broadcast by the BBC. “Oh, no,” they were told. “That is illegal.” But somehow, a radio appeared, and the soldiers and family listened to clandestine broadcasts together.

Then, with the German invasion of Russia, the soldiers told the family they would be shipping out. The Gestapo – the German secret police – would be moving in. “Things are going to get very bad for you,” their new friends told them.

“All those French people in the town,” John said, “Knew what was happening. Already the Germans were making deals with them. They could have warned us, but they said nothing. Our only warning came from two German soldiers who had become our friends.”

Looking back, John and Renée agreed that friendship and even help sometimes came from unexpected places, and that they had accomplished nothing alone. Their determination, smart decisions, and love for each other were invaluable, but they could not have succeeded in getting to Switzerland, surviving the war, or making the good life they have without assistance from friends and even strangers whose paths crossed theirs.

And it’s a risky business, trying to judge who will help and who means harm. It’s possible that a person wearing a uniform that says “danger” is the person to trust, rather than the neighbor whose everyday friendliness masks indifference.

In 2012, John and Renée returned to Europe to commemorate the events of 1941 and 1942, and to honor their families. In Kehl, they witnessed the placement of four “tripping stones” – commemorative tiles set into the sidewalk in front of Renée’s former home. These tiles are set slightly higher than the sidewalk, so walkers cannot ignore them. Each stone bears the name of a family member and the years of birth, deportment, and murder. Renée’s stone alone says, “Flucht 1942 schweiz – überlebt.” Went to Switzerland in 1942. Survived.

“It is different now,” Renée said. “They teach the school children what happened. There were students there, placing red roses by my family’s stones. They want them to know, so it doesn’t happen again.”

At St. Radagonde, in France, a new family has taken over the farm. The new owners showed John and Renée around the place. It originally was a convent, and the Rothschild family had used the small chapel on the grounds as a synagogue. When the Americans came, they saw the chapel from across the river and thought it was a bunker; they shelled it to the ground.

The new owners of St. Radagonde have cleared that space. The foundations of the chapel-synagogue stand now as a border for a memorial they have erected, a beautiful monument naming all the Rothschild family members and their guests who were taken away by the Nazis in July, 1942.

The Rothschild and Bodenheimer families are remembered, and not just by John and Renée, their lone surviving members. They now have American grandchildren and great-grandchildren, nieces and nephews and cousins. And even those in their own communities, where they were betrayed or simply left to fate by the indifference of their neighbors, now remember and honor their legacy of determination, faith, family, and life.

{gallery}Community/2013/042613/rothschilds_042614{/gallery}