[by Shiela Steinman Wallace]

[by Shiela Steinman Wallace]

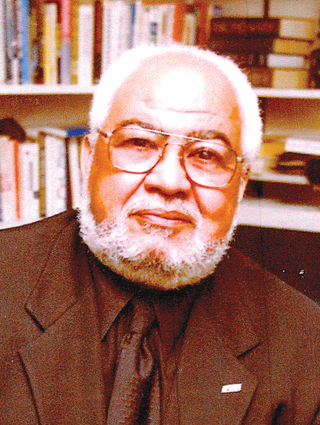

Each year, when the Jewish Community of Louisville chooses an individual to honor with the Blanche B. Ottenheimer Award, the organization seeks a person who has significant accomplishments that positively impact the greater Louisville community and beyond. This year’s honoree, Mervin Aubespin, has been a trailblazer, helping define tolerance in the city, creating opportunities for minorities and educating Louisvillians about the Black community from the city’s west end to Senegal and South Africa.

For many of us, Aubespin is an old friend who greeted us every morning as we opened The Courier-Journal to catch up on the news. For 35 years, until his retirement in 2002, Aubespin was part of our daily ritual as an artist, reporter and associate editor. But if we are to understand his impact upon us, our community and the world, we must look more carefully at his life and accomplishments. He makes it very easy, because he is a born storyteller with an easy-going style and an affable personality.

Born in 1937 in Opelousas, LA, the world Aubespin knew growing up was very different than the one we know today. People were either white or colored, and separation was enforced.

At age 15, he entered Tuskegee University, which he described as “a fine school” in a town of the same name in Alabama. “On the weekends,” he recounted, he and a friend “would go to Montgomery to visit his friend’s aunt and get away from the cafeteria food. She would feed us and we would visit Alabama State University, a Black school, and cruise the campus.

“One day,” in 1955, Aubespin continued, “she said, ‘I’m not feeding you unless you come to church this evening.’” Of course, the two hungry college boys decided it would be wise to go to church.

As it happens, the church’s pastor was the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King was busy organizing a bus boycott. Aubespin and his friend suddenly found themselves volunteering. His friend drove people to and from their jobs while Aubespin matched drivers with riders.

“By 10 or 11, most people would be at their jobs,” he recalled. Sometimes, he and King would engage in conversation while walking around the parking lot. Dr. King helped shape Aubespin’s views on “fairness, diversity and being inclusive of everybody.” The bus boycott proved successful and launched Dr. King as a major voice for the civil rights movement.

In 1958, Aubespin graduated from Tuskegee and moved to Louisville to join his family and seek a teaching position.

By 1961, now teaching junior high school, he became involved in the local civil rights movement at the urging of friends, especially Frank Stanley, Jr., a young, local civil rights leader. He participated in downtown protests advocating for a public accommodations ordinance that would guarantee African Americans the right to eat, enjoy movies and shop without discrimination in downtown establishments.

Aubespin joined King and other leaders in the famed Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, an experience he claims changed him forever.

In 1967, he became active with the Louisville Art Workshop, a group of African American artists who showed their work wherever they had the opportunity. This connection ultimately opened the door to The Courier-Journal for him.

“The Bingham family owned the paper,” Aubespin began, “and it had the reputation of being editorially very liberal. Unfortunately, the newsroom didn’t reflect that liberalness.”

It was C-J art critic Sarah Lansdale, who would cover the Art Workshop’s shows, who told him of an opening in the art department at the newspaper.

When he went for the interview, Aubespin recalled, the department head “wasn’t excited about bringing in an African American on staff,” so “I made him an offer. … I said I would work for two weeks with no pay to see if I could do it and to try it out. He said, ‘I can’t do that.’”

Finally, after a two-hour interview the department head accepted Aubespin’s challenge. He had been there for less than a week, when the man returned to him and said, “Merv, you’ve got the job.”

As the newest artist, Aubespin worked nights and weekends and frequently took his orders directly from the editors. Being naturally curious, he also asked a lot of questions and developed good relations with them – often sharing lunch with them.

In May 1968, he recounted, “there was a lot of tension in the West End” and some people felt the police had been “overly proactive.”

“A well-known member of the community was driving down Broadway,” Aubespin continued, “when he saw a friend being pulled over and searched.” The community member stopped to try to help, and the next thing he knew, “he was on the ground and handcuffed.

“That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Aubespin said. “The community was angry, and I heard in the neighborhood that they were going to hold a rally at 28th and Greenwood.”

Since Aubespin worked for the paper, he brought the lead to his editors and suggested, “that maybe they should send down a reporter to cover the rally. They said it was a good idea.”

Half an hour later, they came back to him and asked him to accompany the white reporter to keep him safe. Aubespin agreed.

“There was quite a crowd, and the younger, more militant people were standing on cars making impromptu speeches about the Police Department and how unfair it was,” he reported.

Aubespin is a keen observer of his surroundings, so he noted that there were police cars close to the rally, but they were keeping their distance, as if waiting for something to happen.

Later, he said, “someone standing on top of a building dropped a Coke bottle. When it shattered, it sounded like a gunshot and police cars came streaming into the place. Soon a group of people turned a police car over and set it on fire. I decided then and there that maybe it wasn’t safe for that reporter.”

Aubespin sent him back to the office with the promise, “I’ll stay and report to you what’s going on,” which he did from pay phones. “You could hear the roar of the cars and smell the burning tires,” he said, and soon that progressed to the sounds of breaking windows and looting.

“It was getting really ugly,” he continued, “and the paper called back and said, ‘we need some pictures.’”

The C-J sent its top photographer. Soon after he arrived at the scene, the cab he was riding in was overturned. The photographer sprinted back to the office and left Aubespin to get the pictures.

The resourceful young man quickly recruited a friend and his own kid brother and hired them as his crew. In the end, Aubespin worked for 48 hours straight, documenting the event that resulted in two dead, many injured, dozens of arrests and thousands of dollars worth of damage. The sheriff, the State Police and the National Guard were all called in, and Aubespin noted, “there was so much tear gas, I could barely breathe.”

At one point, the young reporter had cause to fear for his life. He was calling in a report, and a policeman challenged him, asking what he was doing and telling him to leave the scene – even holding a gun to his stomach at one point. When Aubespin said he was reporting for The Courier, the officer said, “’There are no nigger reporters at The Courier-Journal,’ and he was right.

“I thanked him,” he continued, “because it helped me realize that if there was anything The Courier-Journal needed, it was somebody like me in the newsroom.”

“When it was over, the editors were delighted. They got a story that, under normal conditions, would have been very difficult to get,” he explained.

“A few weeks later,” he continued, “the editor called me in and said, ‘we think you’re worth more to us as a reporter than an artist because you know the community.” The editor pointed out that the same skills of observation Aubespin used as an artist would serve him well as a reporter.

The Binghams didn’t just turn him loose without support. They encouraged him to apply for the Minority Journalism Program at Columbia University in New York City and paid his tuition. He entered the intensive four-month program in 1971. The class of 12 honed their skills with “some of the top journalistic brains in the nation” including Walter Cronkite, Howard K. Smith and Ben Bradley, as well as Robert Maynard and Earl Caldwell, African American journalists who were administrators of the program.

When he returned to Louisville, he was asked how he could best help the community, and he asked to cover the African American community. “Diversity and civil rights became my beat,” Aubespin said. “I knew the players and leaders, and I had a ball.

“For the first time,” he continued, “they had a person at The Courier-Journal they trusted; and they would call me when marches were taking place. … I was their man down there.”

In addition, Aubespin had also developed good relationships with some of the white leaders who were supportive of civil rights activities, like Suzy Post, Anne Braden and Mary Helen Byck.

Aubespin didn’t limit his work to strife and the struggle for civil rights. He also enjoyed writing stories that showcased the richness and diversity of the Black community.

Aubespin thrived at the Courier, and eventually was promoted to associate editor and became the primary recruiter and trainer for new talent for the paper. In that position, he also monitored the diversity of the newspaper’s coverage and administered its internship program for college students.

He also served as an advisor to journalism programs at the University of Kentucky, Western Kentucky University, Howard University, Franklin College, Jackson State University, Florida A. & M. University and the University of Alabama.

A former president, vice president and regional director of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ), Aubespin joined the organization when its focus was getting diversity into newsrooms across the nation. Under his leadership, its membership “grew from less than 300 to over 1,000.” He helped establish its first national office in Louisville and a permanent office in the Washington, DC, area.

He is also the founder of NABJ’s Louisville Chapter and twice served as its president. He is a member of the American Society of Newspaper Editors and has chaired its Diversity and Human Resources Committees; and helped create the American Copy Editors Society (ACES).

As president of the NABJ, Aubespin met Djibril Diallo, “a young man who worked for the U.N. and a native of Senegal. … Diallo had a Ph.D. from the University of London, an M.A. from the Sorbonne in Paris, and spoke 13 languages.” The two became friends.

At the time, the foreign correspondent positions went to senior reporters, and that meant that African Americans didn’t get the overseas postings. Diallo challenged Aubespin to put together a group to travel to Africa “to see the problems and let them interview Africans to see what Africans are doing about the problems.”

In 1985, he did, and it became the first of 15 such trips. For over 20 years, he served as a consultant on media to the United Nations Development Programs Office of Public Affairs, and has served on the U.N. Task Force on AIDS. He has led seminars and traveled to Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Ivory Coast, Mozambique and South Africa. He has met Nelson Mandela and other African heads of state.

Once, Aubespin asked Mandela, “Aren’t you angry about being in prison for so many years?” He said Mandela replied, “I don’t have time for anger. Anger pushes aside what we need to do to make the world a better place.”

As he neared retirement, Aubespin, who described himself as a “clutter bug,” said he began to look at all the clippings from his career and decided to put together a pictorial history. He soon found that his friend and colleague Kenneth Clay had similar plans. They started collecting photos from the archives at The Courier-Journal, the library, the University of Louisville and other sources, and supplemented them with discussions with older citizens about their memories.

They knew that Dr. J. Blaine Hudson, the dean of U of L’s College of Arts and Sciences, had written a book on the underground railroad and local black history. They soon recruited him to their project. The result is Two Centuries of Black Louisville, a Photographic History by the trio, which was published in 2011. With more than 400 photos, some never published before, the book traces the history of the black community from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in 1778 to the time of the book’s publication.

Rather than accept royalties from the book, each of its co-authors has chosen a charity to which the proceeds are directed. Aubespin directs his share of the earnings to a scholarship program ACES established in his name, as well as NABJ’s Aubespin scholarship. Clay’s supports Legacies Unlimited and Hudson’s supports the Saturday Academy.

Aubespin has received many local and national awards for his reporting and his leadership in providing employment opportunities for minorities in journalism, and two scholarships and awards are presented annually in his name. He is a member of the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame and the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame.

Among his many honors, he received the Distinguished Service to Journalism Award from the Association of Schools of Journalism and Mass Communications and the Mayor’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Award.

Aubespin is married to Deborah C. Aubespin, a middle school teacher and a member of The Temple. His daughter, Eleska, a former features reporter, lives in Texas; and his stepdaughter, Sarah Spearing, lives in Los Angeles and works in the movie industry.

The Ottenheimer Award will be presented at the Jewish Community of Louisville Annual Meeting, Sunday, June 24, at the Jewish Community Center. Brunch will be served at 9:30 a.m., and the meeting will begin at 10.