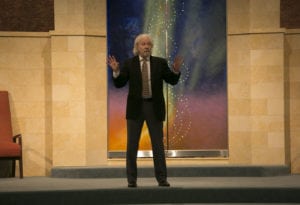

Rabbi Irwin Kula, the president of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership (CLAL) is described as a thought leader who likes to rock the boat. The description proved apt when he came to Louisville for a well-attended open community forum held at Adath Jeshurun on Tuesday, November 29.

To set the stage, Rabbi Kula asked community members to imagine that they lived in the year 160 C.E. The Temple had been destroyed and the way Judaism had been practiced had been destroyed. To ensure its survival, the leaders of the time had to reimagine and reinvent Jewish practice.

They retreated to Yavneh for intense discussions away from the hubbub of cultural chaos and developed the seeds of rabbinic Judaism.

Today, Rabbi Kula posited, we are facing the same kind of disruption and chaos and it is up to us to reimagine and reinvent Judaism to be relevant to the generations to come.

For most of the 20th Century, Rabbi Kula said, the Jewish community had a “basic, coherent narrative that linked us together.” We were affiliated with Jewish congregations. We gathered at Jewish Community Centers to be with other Jews, and often weren’t accepted as part of the general community. We worked together to free Soviet Jews and Israel’s survival was a unifying cause because we knew that the Jewish State would be our refuge should our lives and communities be threatened.

Millennials experience the world very differently. For them, Judaism is not a barrier to full participation in American life, and a recent study reported that Jews are even considered desirable life partners in the non-Jewish community. They are exposed to a wide range of cultures and are used to “mixing, bending, blending and switching” everything from music and food to news sources and the way they watch television and movies, picking and choosing the pieces that are relevant to them.

This applies to Jewish practice as well. “This millennial generation is saying, ‘you know what, I don’t have your baggage, I don’t have the nostalgia. I don’t understand the sentimentality. If it works, I’m on it. If not, don’t worry. I’ll do the six things all Jews do. I will come to Seder, and even when you die, I will still have one. I will light Chanukah candles. I’m not going to say I’ll do it eight days in a row. I may not light them one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. I might do it eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, which is the way Shamai did it, but I will light Chanukah candles. And I will show up for some sort of High Holiday experience.’ ”

These change in practice and affiliation are not unique to Judaism. “The same thing is happening in Catholism,” he said. “One of 10 Americans are lapsed Catholics. Protestant churches are going under.”

In fact, he added, “The fastest growing religious identity is none.” Rather than relying on clergy and religious establishments, young people are inventing their own rituals and they’re approaching their spiritual needs like they approach shopping. If one source doesn’t offer what they want, they go to another, and much of what they do is collaborative.

This demonstrates that the community doesn’t have an identity problem, he explained, but if existing institutions don’t change and reimagine their offerings, we will lose the next generation.

“Louisville,” he continued, “has the possibility of being Yavneh.” The population is large enough for people to work together and come up with new approaches, and, he said, the stakeholders don’t say, “Do it my way or I’m going to take my marbles and go,” thus holding the community hostage.

Kula identified two metrics from Torah for all things Jewish as identified by Maimonides: “The welfare of the soul and the welfare of the body – tikkun hanefesh and tikkun haguf. …That’s the purpose of Torah. Every piece of Torah has to be refracted through helping you, then helping others gain existential truth.”

Seeking these truths and finding ways to help ourselves and others are the things that matter.

In a community of 8,500 Jews, Kula observed, everyone knows the leaders. The downside is everyone knows everyone’s triggers and weaknesses, but there is also an upside. “We need to give each other the benefit of the doubt,” he said, “and we need to fund failure.”

By that, he means we need to experiment and discover what works. “It’s messy,” he added, “but it’s how we grow.” We don’t know what the world will look like 170 years from know, he concluded, “but if you do this in Louisville, people will say you lived in one of the historic ages” like the rabbis in Yavneh.

David Kaplan, representing the Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence, which provided the funding made this program possible, introduced Rabbi Kula. JHFE’s grant is designed to bring the community together and also includes support for continuing consultations with Rabbi Kula.

The Jewish Federation convened a Steering Committee made up of clergy and executive directors from Adath Jeshurun, Jewish Family & Career Services, Jewish Federation of Louisville, Jewish Heritage Fund for Excellence, Keneseth Israel, Temple Shalom and The Temple. Together, they worked with Rabbi Kula to plan his visit to be of maximum value to the community and will continue to consult with him to move the community forward.

While he was in Louisville, Rabbi Kula also met with Jewish community professionals and Board members.